Empty Tombs: Rachael Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures give emptiness a body. Most of the time, the space between things so fills our vision that it registers only as nothingness: perspicuous air, bright and vacant. Whiteread takes that nothingness and floods it with substance – plaster, resin, concrete – casting it, rendering it massive. She makes a fossil of the emptiness between, preserving and petrifying it. She lends it weight, reveals its sheer and massive thereness.

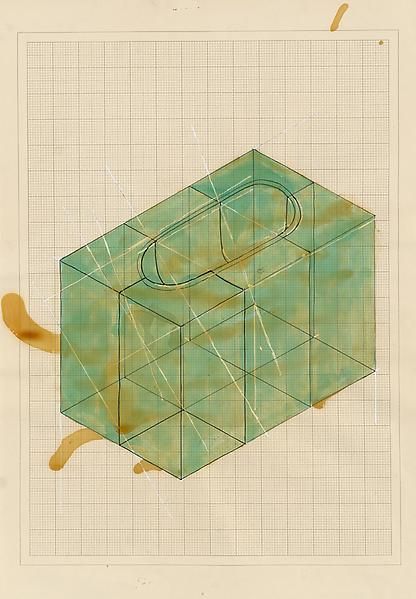

I was obsessed with Whiteread in the year I spent at art college. I made casts of the insides of boxes, banana skins, paper bags, clothes, the mess around the studio. In a half-hearted bid to be less derivative I started making hybrids, crossing Whiteread’s casts with Sarah Lucas’ stuffed tights. I filled wooden boxes with jumbles of the padded tights, draped them in plastic, then poured gallons of liquid plaster into the gaps and left the whole block to set solid. I enjoyed the strange discovery of coming back to the studio to break apart the wooden shuttering. It was like the discovery of drawing: see the negative spaces, render the positive masses strange, begin to see them afresh. I took great pains making plinths for them for our final show. They looked like the Parthenon marbles, and like giant, riddled Swiss cheeses. Whiteread was teaching me to pay attention to the space between things. I began to see that absences matter.

Her own work is less organic, more architectural. Is there not something oppressive about the monumental pieces? I imagine the enormous weight of the concrete inside the foursquare mass of Ghost (1990) searching for escape, pressure forcing it to corners and cavities. But the secret to Whiteread’s work is to look past the imposing monumentality of it, to focus instead on the edges, the particular details, the granular fringes. When space takes on a body its heft and bulk become visible, but so does its intimacy with the edges of things. We discover that the space of a room reaches all the way into the door’s keyhole. The space around a set of bookshelves feels its way over and around the books, leaking between covers and flypapers, behind spines. No detail is altered, edited, obliterated or ignored. Rather, each and every fold of texture is accepted, registered, and understood. What seemed like oppressive pressure is in fact an insistent but infinitely accommodating attention.

These days, I often turn to Whiteread’s work for a way of imagining divine love. A love which, with an evenness of attention, an irrepressible equality of regard, accepts all things, embraces all things, registers all things. A love that combines a kind of monumental weight with an infinitely particular touch; something with a geological, unstoppable force – but with a surface so accommodating and so intimate as to notice and embrace the grain in a piece of wood, the dusty rubber-bloom of a hot water bottle, the spiral joint inside a cardboard toilet roll, the sooty residue in the back of a fireplace. The plaster around the hollow spines of the books is stained with color from the covers and bindings. Whiteread loves these transferences of patina, color and texture, the fresco-like ghosts they leave in the plaster, and I cannot help imagining this printing, this knowing, as itself a kind of love.

The sculptures help me to hold on to a love at once so general as to embrace all things equally, and so particular as to know all things intimately. Such a love is scarcely imaginable: all our references are human, and human love is so often a zero-sum game – loving this more than that; loving so as to push other lovers out of the way; loving things as prelude to trying to change them. The sculptures help because they offer an image for a different kind of love, utterly enveloping, utterly accepting. They help me to imagine divine attention pooling around and pressing up against things: like plaster in the casting, it feels its way around all our minuscule textures and imperfections, registering and accepting them. Without protest or reply, with silent delicacy and insistent weight, divine love takes on the shape of things. And things seem more themselves for having been known like this.

*

The world has so much texture and detail to be loved. I often think of Annie Dillard’s writing on this theme. Dillard has a sculptor’s feel for shape. She considers the texture of the planet as a whole, characterized by its jaggedness, its mountainous protrusions and its frayed fringes, its surface more a pitted and prickled pineapple than a sphere.

She imagines a relief globe detailed enough to map the whole planet. It would register, in perfect miniature, the furrows in tree bark, ‘the free standing sculptural arrangement of furniture in rooms, the jumble of broken rocks in a creek bed, tools in a box…’. (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, 2011, p.140)

Again, in Holy The Firm: ‘the sky clicks securely in place over the mountains, locks around the islands, snaps slap on the bay. Air fits flush on farm roofs; it rises inside the doors of bars and rubs at dull barn windows. Air clicks up my hand cloven into fingers and wells my ears’ holes, whole and entire.’ (The Abundance, 2017, p.40)

I find the same feeling in Gerad Manly Hopkins’ poem The Virgin Mary Compared to the Air We Breathe:

Wild air, world-mothering air,

Nestling me everywhere,

That each eyelash or hair

Girdles; goes home betwixt

The fleeciest, frailest-flixed

Snowflake; that’s fairly mixed

In every least thing’s life…

… rich, rich it laps

Round the four fingergaps…

Thinking with Dillard and Hopkins, I imagine a Whiteread-style cast of the whole world in negative. The shape of the air laced through the plants captured in monumental plaster, with minute negative sockets fitting even the needles of pine trees; positive branching networks flooding chimneys and drains, sewers and gullies, even the alveoli of the lungs. The complexity of the imagined positive shape is bewildering. Every leaf and twig has its delicate sheaf of space closed around it. Every nostril, every crevice, and every burrow is the beginning of an ever more fractal delicacy.

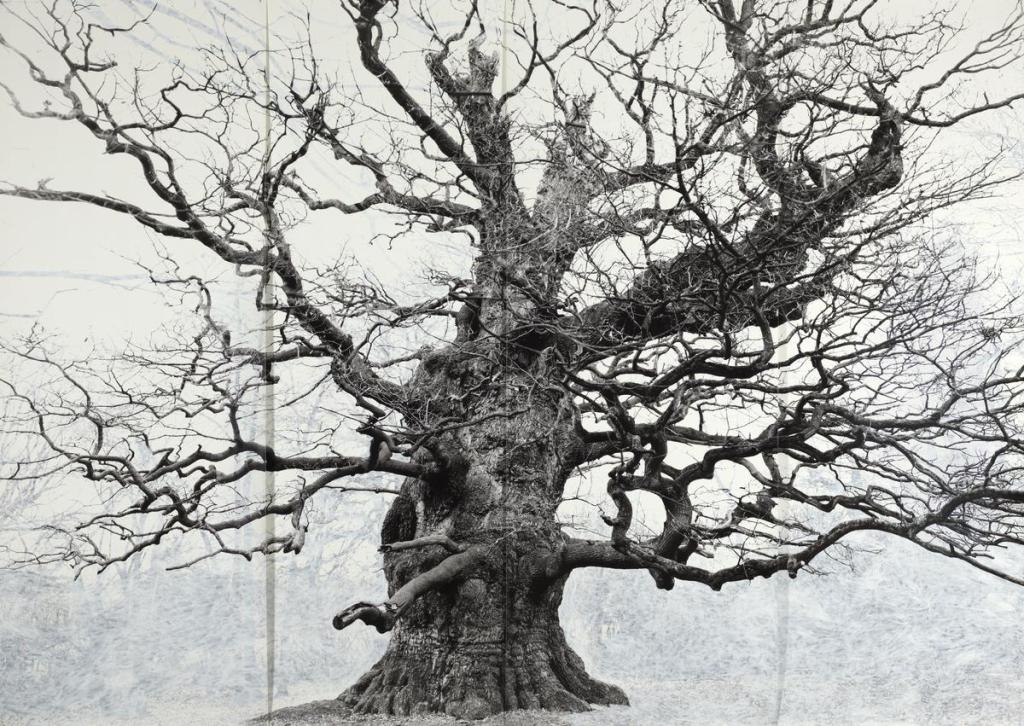

Walking through the park I imagine the patterns the trees would leave riddling through the casting material. The wind shivers and shakes the leaves and the whole arrangement shifts, the negative spaces reorganizing, and I am conscious again of space’s hospitality, its provision for endless rearrangement. Without lag or delay, airy light has rearranged itself to pool differently around these branches, accepting them again. Simone Weil imagined the doctrine of creation this way, spatially: God withdraws in order that the world can be. God’s own infinite life somehow limits itself, pours itself out, to make room for something other (Gravity and Grace, 2002, pp.33,41). For Weil, God’s absence from creation is necessary, generous, hospitable. Perhaps God withdraws just far enough, but not further: ceding us space, but filling the absences, the invisible hugging and exactly fitting the visible, as air fits and fills a lung. I think of Tacita Dean’s painted tree photographs, especially the grand oak Majesty. Dean fills all the not-tree spaces with gouache absence. The portrait here is not of the tree but of that bewilderingly delicate absence. Something crackles to imagine the two together, positive and negative, perfectly fitted to each other.

*

‘Fit’ is a sculptor’s stock-in-trade, their method and their material. What fits where, what goes, what works? Whiteread’s sculpture takes this sense of fit not only as its method but as its subject. The casts are studies in fit, portraits of fit.

Perhaps there is a sense in which God fits the world. ‘Here I work in the hollow of God’s hand…’ begins Alice Oswald’s poem Prayer (The Thing in the Gap Stone Stile, 2007). That hollow fitting and enfolding us, even as exactly as a cast. How beautiful it is that God’s hollows accept and fit all our unshapeliness. In fitting and accepting our furrows and imperfections, we find that even our difficulty and our frailty somehow fit. Sin, as theology has traditionally called this difficulty of texture, is itself somehow fitting: it befits us, because God fits our sin, accommodates and accepts it. And somehow the texture of this fitting is more beautiful than a featureless perfection would have been.

‘Fit us for heaven’, asks the carol Away in a Manger, even as it describes that most unimaginable fitting, of infinite divine life to finite human life in the incarnation. ‘Fit’ is a wonderfully ambiguous verb here, meaning both ‘make ready’ and ‘conform to the shape of’. The surprise is that God does the work of fitting us for eternal life (making us ready) not first of all by reshaping us, but by fitting divine life to us (conforming to our shape). It is only God’s fitting us, God taking our shape, God accommodating our furrows, that can make us fit, in the sense of being ready. We are not the sculptors of our own salvation: it is God’s fitting to us, God’s loving acceptance of our shape, that enables all our growth. Trusting the accepting air, we can feel our way forwards.

Gerard Manly Hopkins again:

I say that we are wound

With mercy round and round

As if with air…

*

Like fossils, Whiteread’s emptinesses carry prints from the past. The grooved surface of every destroyed book is registered with intimacy and precision, each block of pages remembered even as it is transfigured.

‘Register’ is another good term for thinking with these objects. Printers use it to describe the precise alignment of matrix and print: a print correctly registered is one where the layers of different blocks are properly aligned, each new impression layered in place on top of the others. We also use the word to describe memory and comprehension: something registered is something known, committed to memory, understood. It leaves a print in us.

Whiteread made her bookshelf casts while developing her design for the Holocaust Memorial in Vienna’s Judenplatz. The finished monument extends similar ranks of shelves around an oblong room, a library echoing a gas chamber. The millions of pages of the books are missing, yet the impression of each is legible in the grooved surface. The preparatory plaster studies of shelves are even finer in this regard than the finished monument’s concrete: the plaster flooding the shelves is encompassing, unsparing, but fine-grained in its attention. The plaster remembers everything, even as it transforms and transposes it. Nothing is finally lost.

Absence can sometimes heighten a presence. I am thinking now of Seamus Heaney’s sequence Clearances, memorializing his mother, and the image he uses in the final sonnet, VIII, of his loss as the space left by a felled chestnut tree:

…a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place …

Its heft and hush become a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

The objects and structures around Whiteread’s absences have likewise each become a ‘bright nowhere’. But they have also, as Heaney says of his mother in the previous sonnet, been ‘emptied/ into us to keep’, leaving marks, leaving lasting impressions. Their ‘heft and hush’ somehow endures. In the word ‘ramifying’, Heaney offers a great arboreal, fractal image for the way things (and especially people) ripple and branch outwards, continuing to leave prints in the world after their absences. Even an empty tomb can be ‘utterly empty’ and yet ‘utterly a source’.

Whiteread’s casts, altogether, give me something to hold on to when imagining God as spirit. I like that they insist on the thickness of space, breath, and memory. So much about them echoes traditional metaphors for the Spirit’s action: the fluid imagery, pouring and flowing; the sense of intimacy and attention, of knowing the world from the inside out; the ability to render things strange; the paradoxical mixture of delicacy and monumentality, gentleness and force. Whiteread herself often reaches for the airy language of breath in her titles: hot water bottles titled as ‘torsos’ become stilled chests; Ghost (1990) thickens the air in a locked room; Shallow breath (1988) takes the space beneath a mattress and leans it up against a wall, the breathing of illness become a kind of healing. In each case, the stilled sculpture recalls the living rhythm of bodies, the filling and the emptying that binds us to the world and to each other.

After spending time with Whiteread, paying attention to absences, I find that ordinary things seem deeper, thicker, more precise, more themselves. It is again possible to glimpse a world cradled and enveloped, surface for surface, cheek to cheek, by an accepting attention. A world being let be, delicately and deliberately itself. In such glimpses, there is no distance between being, and being known, and being loved. They take up the same space. They fit each other exactly.

Easter 2024